In Game 4 of the 2022 World Series, Cristian Javier delivered a masterpiece on the strength of a single pitch. Over six innings, Javier threw 70 fastballs, struck out nine hitters, and allowed zero hits. The fastball only averaged 93 mph, but the Phillies still couldn’t time it up. Javier’s ultra-flat vertical approach angle and elite induced vertical break (IVB) created the illusion that the pitch was defying gravity. The Phillies called it “the invisible fastball.” His catcher called it the best fastball in the sport.

Javier might now have some competition for that title. Clearly, he and Cubs rookie Shota Imanaga are in a class of their own — they’re the only two starting pitchers with at least 90th percentile IVB and VAA (vertical approach angle) on their four-seam fastball. But Imanaga is besting Javier in one key respect: his ability to consistently locate the pitch in favorable spots. For that, he can thank his mastery of the vertical release angle.

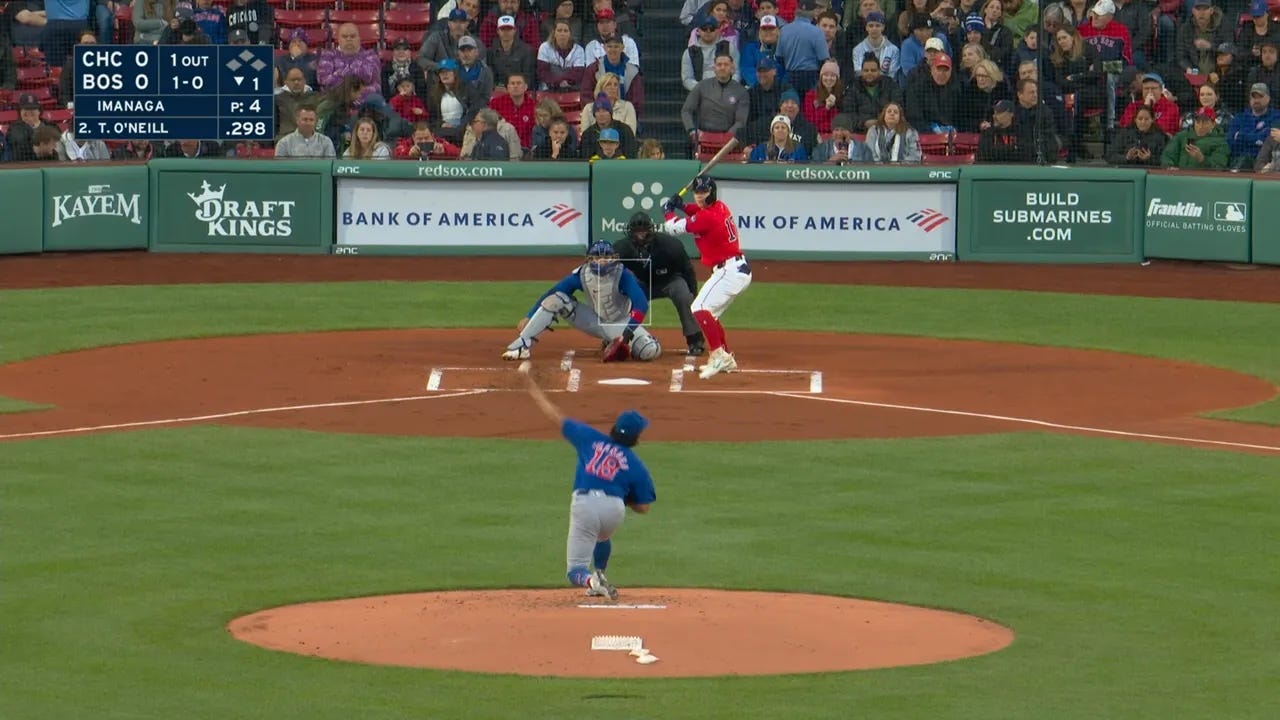

Behold Javier and Imanaga’s release angle pairs thus far in the 2024 season:

Imanaga’s elite command is evinced by the density of his release angles. He ranks among the league leaders in the Kirby Index, a statistic that measures how frequently a pitcher repeats their fastball release trajectory. Imanaga repeatedly releases his fastball with a vertical release angle (VRA) between -1° and -1.5°, the exact VRA necessary to throw high in the zone from his 5.5 foot release height. The combination of a deceptive shape and pinpoint command has made it the single most successful pitch of the 2024 season — and the engine powering one of the best starts to a career in MLB history.

A fastball like Imanaga’s is uncommon because it requires a series of traits that are difficult to combine in a single pitch. First, in order to create a flat approach angle, a pitcher must throw from a low release point. But the lower the release point, the harder it is to throw high in the zone — after all, the pitcher is closer to the ground. If a fastball is thrown at a league-average VRA of -2° from Imanaga’s release height of 5.5 feet, it’s going to end up in the middle of the plate. Other low-release pitchers get around this by throwing sidearm, angling the pitch at a 0° VRA — completely level — at release. But that delivery modification comes with a tradeoff: Fastballs released from a sidearm slot rarely have above-average induced vertical break.

In order to throw a fastball high in the zone from a flat release angle and still maintain high IVB, the pitcher must get mechanically creative. I speculate that there are two significant ways that low release height pitchers alter their vertical release angle to elevate their fastball: They change the angle of their elbow relative to their shoulder and the position of their hand on the ball. The effect of tweaking these variables on VRA might look small, but the influence on the ultimate location of the pitch is enormous: a 1.5° change in VRA results in roughly a two foot difference in the vertical location of the pitch, which is the difference between a fastball at the top of the zone and one at the knees.

In most cases, it appears that extraordinary arm angle manipulation is required to create this unlikely combination of a high fastball with good IVB from a low release point. Prime Craig Kimbrel is a textbook example.

These days, Kimbrel nearly throws sidearm, so his IVB isn’t where it was in the mid-2010s. But back then, Kimbrel kept his shoulder parallel to his elbow while still throwing from a three-quarters release point from the elbow up, generating -1° VRAs with above-average IVB. Check out this 2016 delivery of a four-seamer to Jose Altuve:

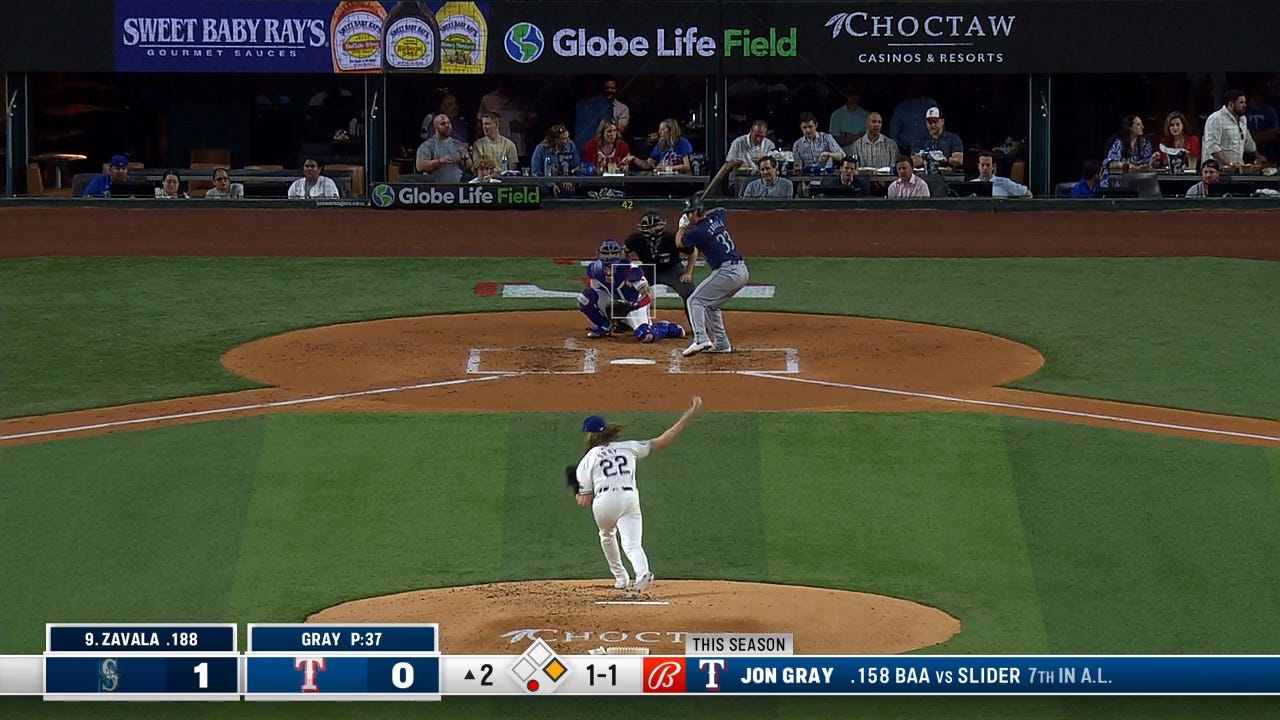

That distinctive crooked-arm delivery appears related to the ability to elevate fastballs from low release heights. Here’s a couple of 2024 examples from Jon Gray and Shelby Miller:

Pitchers with higher release points, by contrast, have the luxury of hitting the top of the zone with a steeper downward VRA, usually between -2.5° and -3°, as opposed to the -1° to -1.5° of Imanaga. Justin Verlander is a classic example: Because he is releasing the ball from seven feet in the air, he doesn’t need his elbow to be parallel to his shoulder to hit that top line:

Verlander’s steep approach angle comes at a cost — it isn’t as deceptive as a fastball from Shelby Miller, Cristian Javier, or Shota Imanaga. But a flat approach comes with its own problems: To throw high in the zone, it’s generally necessary to either incorporate a sidearm delivery or throw like 2010s Craig Kimbrel.

Shota Imanaga suggests there might be a third option. Someone with more mechanical knowledge than I would need to confirm this, but it looks like Imanaga creates a truly unique arm angle to access his -1° VRAs and therefore throw high in the zone. Like Kimbrel, his elbow stays mostly parallel to his shoulder, but unlike Kimbrel, his arm keeps a consistent shape in what could only be the product of remarkable flexibility. Unlike with Kimbrel, Miller, or a number of other low-release pitchers with good ride on their fastballs, there is no distinct break in the chain between Imanaga’s shoulder and his hand:

Imanaga’s arm angle is only one possible contributor to his ability to throw high in the zone. Another is the strength of his fingers, deployed to generate high spin (and therefore good IVB) on his four-seamer.

In 2018, Saul Forman, now the lead quantitative analyst for the Phillies, speculated that there is a strong relationship between getting “behind the ball” and generating high spin. He shared visuals of Gerrit Cole, noting that Cole’s spin rate increase corresponded with the adoption of both a Kimbrel-like arm angle and a clear intent to throw “through” the ball instead of “around the ball.”

A close look at two Imanaga releases — one (left) where the pitch finished at the top of the zone, one (right) where it finished at the bottom — provides a visual understanding of what that might look like.

In the photo on the left, the top of the ball is much more visible than in the photo on the right. On the left, Imanaga is “behind” the ball, stretching his fingers as far possible in order to snap the ball off the seams. On the right, Imanaga is “around” the ball, driving the pitch downward.

In any case, it seems clear that Imanaga’s invisible fastball rests on a foundation of well-rounded athleticism. Last week, I asked Jim Wagner, who runs the ThrowZone Academy in Santa Clarita and has worked with a number of major league pitchers, how Imanaga gets to his outlier release angles. Wagner noted that Imanaga not only has a “special lower half” but also super flexible hips.

“If you have instability or your hips don’t have a great range of motion, that will (keep you) from getting out to a lower release point,” Wagner told me. “(Imanaga is) very, very good with his lower half but he’s even better rotating his hips before his shoulders rotate, (getting) tremendous hip and shoulder separation. And his hip allows him to get out to that release point. You have to be super strong to do that.”

At this point, we are deep down the mechanics rabbit hole. Perhaps we can now poke our heads back up and reflect on the improbability of this pitch by comparing it to those of Imanaga’s peers.

There are other four other pitchers with an average release height of 5.5 feet and 150 fastballs thrown this season — DL Hall, Logan Allen, Pablo López, and Jon Gray. Their average “hiloc%” — percent of their fastballs located high in the zone — is 42%; their average IVB is 14.4 inches. Imanaga is hitting the top of the zone 58.5% of the time with an average IVB of 19.3 inches.

Nobody in baseball throws a fastball with this combination of deception and command. The pitch is a unicorn — and Imanaga is riding that unicorn to a magical start.