To earn his contract, Taijuan Walker does not need to be a star. At $18 million a year, the Phillies just need him to be the same guy he’s been since his first full season with the Mariners in 2015: A durable “innings eater” with a so-so ERA.

But Taijuan Walker is no longer the power pitcher of his youth. In 2015, Walker averaged 95 mph on his four-seam fastball and threw it 63% of the time. These days, his four-seamer sits around 91 mph, and he throws it less frequently than his sinker, splitter, and what I’ll call his lateral breaking ball. (More on that later.) In lieu of power, Walker has become a master of deception, chasing weak contact with a six-pitch “kitchen sink” approach.

Walker isn’t just deceiving hitters; he’s also confusing machine learning algorithms. Stuff+ gives Walker’s slider a grade of 17, saying that it is by far the worst slider in baseball. Dylan Floro, at 60, is the closest pitcher to Walker as of June 6. (League average is about 112.) PitchingBot, meanwhile, gives Walker’s slider a 29 on the 20 - 80 scale.

What’s weird is that the slider has been his best pitch this season. The run value on his “slider” is at -1.5 runs per 100 pitches, ranking comfortably above the MLB average for the pitch type1. What’s going on?

One place to start might be Walker’s pitch plot. It’s like a rainbow of pitch shapes:

There is no significant gap between his slider (gold dots) and sinker (orange dots). Bizarrely, he will even throw a “wrong way cutter” that drifts to his arm side; on the plot, it connects his sweeper to his four-seam fastball like a bridge across shapes. So it’s not just that Walker throws six different pitches; it’s that he creates a constant state of confusion about which pitch is coming out of his hand by blending the shapes together.

When the models grade his slider as the worst in baseball, it’s mostly because it isn’t thrown particularly hard and stays at roughly the same vertical height as his fastball — not generally a recipe for success. But I think these models are missing something. I don’t think he’s just throwing one slider with one distinct shape; to my eye, he’s throwing somewhere between two and infinity sliders.

I figured that the lack of differentiation between his various sliders explained the disagreement between its run value and its Stuff+. To test this, I performed a K-Means clustering exercise on every Walker pitch that moved more than zero inches to his glove side, which essentially meant that I cut out all of his “wrong way cutters.”

My best guess was that he was throwing five distinct sliders. So using K-Means, I created five groups based on shared velocity and horizontal movement characteristics. Here they are color-coded by cluster, with velocity on the x-axis and horizontal break on the y-axis:

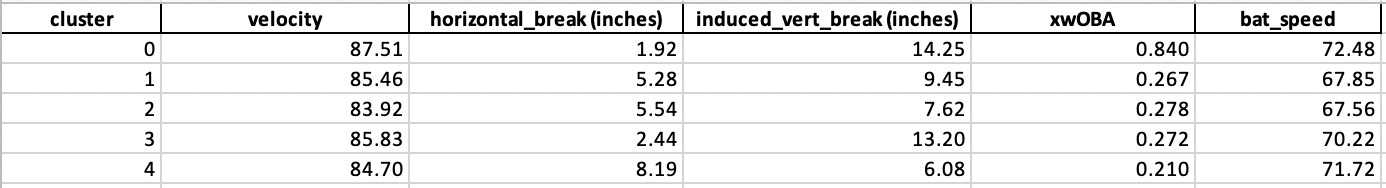

To me, these groups look pretty distinct. He throws a slower and bendier sweeper (cluster 4), a slow slider with less break than the sweeper (cluster 2), a slightly firmer slider (cluster 1), and a subtle cutter with just a couple inches of horizontal movement (cluster 3). And then there’s cluster 0 — the cement mixers.

As you can see on the table of stats and on the K-Means plot, cluster 0 pitches go faster than his other lateral breaking balls and break between zero and two inches horizontally. In other words, it mostly moves like a bad cutter.

Looking at contact quality as defined by xwOBA, Walker has succeeded with the breaking balls that aren’t in cluster 0. Even cluster 3, the other cluster that looks like a cutter2, is inducing below-average contact quality, exactly what Walker is looking for from that pitch. But in cluster 0, hitters are “letting it eat”; he’s allowed a .840 xwOBA on cluster 0 pitches, including two home runs and two doubles.

So far this season, Walker’s constellation of movement has largely kept right-handed hitters off balance, especially when he gets somewhere between four and six inches of horizontal movement on the pitch. In clusters 1 and 2, for example, the average bat speed drops to roughly 68 mph, well below the major league average on sliders, which might reflect uncertain swings. My guess is that the random number generator nature of his slider makes it hard for hitters to sit on a particular shape, allowing Walker to generally stay off the center of the barrel.

But sometimes the random number generator spits out a cluster 0 slider, which I’ll call a cement mixer for the rest of this article to avoid confusion. Cement mixers go faster and move on more of a straight line trajectory than the other four lateral breakers defined in the clustering exercise. Perhaps unsurprisingly, cement mixers also spin the least of any cluster category.

When the ball comes out of Walker’s hand wrong and spins maybe one fewer rotation than it should, it is basically the worst hanger you could imagine, traveling at 87 - 88 mph with no movement. Here’s a cement mixer that Nolan Gorman met with a massive swing:

On a 2-0 count, Walker is probably hoping to get the ball in on Gorman’s hands, jamming him and inducing a weak pop-up. Instead, the pitch stays up with no movement, and it gets crushed.

It looks like Walker had a similar target on the cement mixer he threw to 0-0 to Jake Cronenworth in his first start back in April. Cronenworth does not have elite bat speed — his average is 69 mph, on the slower side of major league regulars, and unleashes a “fast swing” of 75 mph less than 5% of the time. On this pitch, however, he unleashed a full-confidence “A swing,” swinging the bat 74.6 mph on this particular pitch as he mashed it into the right-field seats.

To paraphrase Billy Beane, Taijuan Walker’s shit doesn’t work when he makes mistakes. He’s living on the edge with little margin for error. But it’s been impressive the extent to which he has been able to make his slider work. A pitch traveling at 84 mph with 7” IVB and 5” HB, in a vacuum, is not really MLB quality, or at least the Stuff models don’t think so.3 But what the model might not fully consider is Walker’s undeniable gift to throw any type of slider at any point — and what effect that might have on a batter’s ability to time up an otherwise unremarkable pitch.

I put slider in quotes because I’m not exactly sure how Stuff+ is grouping his pitches. My best guess would be that it’s a mix of sliders and cutters.

86 mph, 13” IVB, 2.5” HB

I should note here that Thomas Nestico’s Stuff model thinks Walker’s sweeper is pretty good.